It is Easy to Be Brave From a Distance

The famous lone protester at Tienanmen Square, 1989

I saw the title of this post on a local veterinarian's sign today. Apparently it's from Aesop's Fables, though I'm not sure which one.

One of my best-received articles was the one I wrote last year on courage. At that time I said that I disbelieved most of the common wisdom about courage: That it's in all of us, that it's false bravado, or moral strength, or superior character. I ascribed it instead to love: "If you love life, others, your world, enough, perhaps you can summon up the courage to do anything." And I agreed with this wonderful quote from right-wing blogger Bill Whittle:

And in this imperfect, flawed nation of ours, perhaps more than anywhere else on Earth, I think about the courage it takes to be poor, to face that sickening knot of worry and despair that comes with not having the money to pay your bills. For there is no more steady and enduring courage than that of a poor family, especially a single parent, who fights a never-ending battle of brutal hours at miserable pay, of perennially unrealized dreams, and of the desperate, numb agony of disappointed children. For people like that, who force themselves to work two jobs while we sleep, to avoid the temptations of crime and dependency while surrounded by luxury and wealth the likes of which man has never knownÖwell, that is dogged courage of a sublime nature that passes all understanding.

And I wondered aloud why day after day, despite my passionate beliefs about what was wrong with the world and what needed to be done, I sat at the computer, and wrote instead of acting. Did I not love the world, Gaia, and its needlessly suffering people and animals enough?

Since then, I've received some solace and, at the same time, a prod, from philosopher John Gray, who has persuaded me that no amount of energy, organization and ingenuity is going to prevent the end of civilization by the end of this century, but has also refocused me on what I can do and should be doing to make things better here and now at the local level, and to create some working models of intentional communities and community-based enterprises and economies that can help those who survive the end of our civilization to live in peace, harmony and comfort.

Supposing you were suddenly blessed with a benefactor who offered you $200,000 per year tax free for the rest of your life. The only condition is that you not accept any money from any other source for doing anything. If you work, it has to be for free. if you gamble or invest, any gains have to be given away. What would you do? Just retire and 'do no evil', living a life of ease with loved ones, minimizing your footprint? Write the book you've been putting off? Do work for charity — locally? in an inner city or impoverished rural area near you? in a struggling nation? Study and learn and make yourself a better person, and then take it from there?

OK, now I'm going to change the supposition. Now you have instead a one-month sabbatical, $25,000 to spend, and a guarantee that your job or other source of income will be intact once the month is over. Same conditions on other income during that month. Would that change your answer? If so, why?

Back to the first scenario. It's now a month later. Honestly, have you started yet, or are you still thinking about it, unwinding, "in transition"? What's holding you back?

Now, just to up the ante, add to both scenarios a $10 million grant that you can spend on any one project, with the proviso that neither you nor any family members can directly personally benefit from the money. What do you spend it on? I'm willing to bet that you make faster progress spending the money than you do changing your lifestyle. If I'm right, why is that?

Here's my answers to the questions above, and why I think they're probably close to what most people would do:

I would start by writing my three or four books: First clean up Natural Enterprise, a book about models for establishing your own joyful, socially and environmentally responsible business. Then my novel The Only Life We Know, which tells the story of a model for intentional community. Then the book The Gift Economy, which outlines a model for a new community-based economic system. And finally, perhaps, The Cost of Not Knowing, a book that explains why we choose not to know or act about huge potential dangers.

I would start by writing my three or four books: First clean up Natural Enterprise, a book about models for establishing your own joyful, socially and environmentally responsible business. Then my novel The Only Life We Know, which tells the story of a model for intentional community. Then the book The Gift Economy, which outlines a model for a new community-based economic system. And finally, perhaps, The Cost of Not Knowing, a book that explains why we choose not to know or act about huge potential dangers.

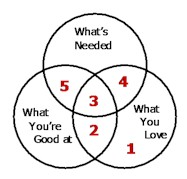

The reason I would do that is that, if we're wise, we do things that are at the intersection of what we're good at, what we love doing, and what's needed. The market, I think, doesn't yet know that the world needs the models I outline in my books, so they won't, right now, pay me for writing them. My 'benefactor scenario' would solve that problem for me, moving the writing of these books from intersection 2 to intersection 3 in the chart at right — and ending my procrastination.

Once these were written, I would start working full-time and simultaneously on making AHA! a reality, creating a new Intentional Community, and facilitating the creation of Natural Enterprises by young people — for the same reason: these activities would then be in intersection 3 for me. There are some other things on my Getting Things Done list bit they're things I'm not good at and would need a lot of time to become good at. Even under this scenario I know these would never get done, though I expect I would spend some time acquainting myself with people who are good at these things.

In the second scenario, with only a month, I fear I would be much less likely to do much different from what I'm doing now. A month isn't enough time to make a significant change in what we do, if we know we have to go back to former behaviours at the end of it.

The $10 million grant would be easy to part with: It would be simply a matter of deciding whether to finance AHA!, or a new Intentional Community, or a 'school' to 'teach' Natural Enterprise, or a new animal welfare organization — or all four. In a month, the money would all have been given away.

Why? I believe it is human nature (a) to only change when we have to, and (b) to avoid risk until and unless the current pain is high enough that the fear of changing is less than the anguish of not changing. There have been a number of studies that confirm this to be true for most of us. Lack of money (and the fear of not having enough) are currently holding me back from jumping into my writing and then real model creation, bringing the subjects of my books to fruition in the real world. For me to give up the current comforts of home, routine, and lots of time with family, for a cause, no matter how worthy, will only happen when either my intolerance for the status quo gets much higher, or the (financial) risk of that change gets much lower. In this scenario that financial risk is lowered. And giving away money for something you believe in, when if you do not give it away you lose it, is easy — you have nothing at risk and you do not have to change.

Does that mean I lack courage, for not doing it now, anyway, with no benefactor or safety net? Perhaps, but I'm not so sure. Look at the best-known heroes of history and myth. They fought for what they did because the anguish of not changing was so high and so immediate, that they had no alternative but to be brave. There was no distance between them and the demons they fought and vanquished. There was no choice but to change. They had nothing to lose.

And how about the poor, the ones that live with this anguish every day? They are of course brave, because there is no distance between them and the grinding daily struggle to survive and make a life for themselves and those they love. The fact that they have no choice but to be courageous does not diminish their courage. It simply explains it.

If I lack courage it is perhaps not daring to eliminate the distance between me and the potential sources of anguish that might raise that level of anguish to the point I might do something heroic. If I were to go to Darfur and see how the people there are living, if I were to see first hand how animals in factory farms and laboratories are treated, if I were to witness the day-to-day misery of the poor and suffering living just a few miles away, that might change everything. That would change everything. My risk aversion, or cowardice, prevents me from staring that truth in the face, because I know I would have to do something, anything, now and for the rest of my life, if I really knew what I fear is happening now in our world.

That is my Cost of Not Knowing, and the reason that, for now, I keep my distance. There is no courage in that, but also no shame. I'm merely human, after all.

This entry was posted in Our Culture / Ourselves. Bookmark the permalink.

Source: https://howtosavetheworld.ca/2005/11/14/its-easy-to-be-brave-from-a-distance/

0 Response to "It is Easy to Be Brave From a Distance"

Postar um comentário